|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

Click on a cover to read the article.

By Bryson Lang

By Bryson Lang

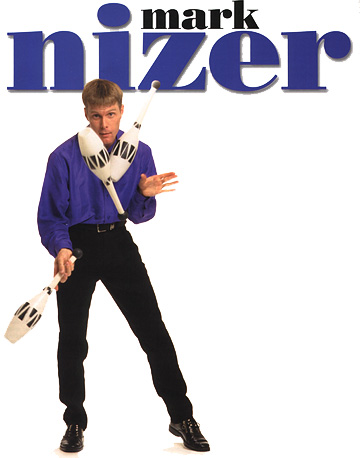

Mark Nizer is serious about juggling, but he doesn’t take juggling too seriously. Anyone who works on the legendary Francis Brunn “Up the Leg” trick for two decades can certainly be considered committed to the craft. However, regarding the cigar box routine in his show, Mark admits in partial jest, “I’m essentially just a geek playing with blocks.”

Self-deprecating humor, self-awareness, and a slightly dark side are just a few aspects of the award-winning act that have entertained Nizer’s audiences for over 20 years. More specifically, uniquely entertained. Yes, you will see a man juggle clubs, balls, and rings (elements of a purist); you will see a man juggle three different awkward items (elements of an ex-street performer); and you will see a man perform with toilet paper, spinning lasers, and a running carving knife (elements of a madman). There are many dimensions to Mark Nizer’s juggling. There are also many dimensions to Mark Nizer.

How did it all start? How does a zoology major from Concord, Massachusetts end up touring with Bob Hope and Barry Manilow? Rumor has it that he met some fairly influential and powerful “family” people during a brief stay at “the institution.” Perhaps he sold his soul to the dark side. Well, darker side. Or maybe he is simply just a very talented, creative, driven man, and a worthy recipient of his successes. For the time being let’s tell Mark Nizer’s version of the story… if that’s his real name.

At 13 years old, Mark,

his twin sister, and his brother, took a juggling class. From that point on

Mark Nizer, later known as Nizer (so, it’s not his real name), diligently

developed a very identifiable and dynamic style that he continues to hone

by practicing daily when possible. You may notice that when Mark practices

in a room full of other performers many, if not most, eyes are on him. He

has a quality in his movement and performance that demands your attention.

Street performing is where Mark “got his act together.” San Diego’s

Balboa Park was the setting for the majority of that phase of his life. It

was a significant starting point that gave him an important education in how

to create an act and how to keep an audience.

“Street

performing was very valuable for me,” says Mark. “It was like being

paid to go to school. You learn fast in that environment, and it helps you

to relax since there aren’t any real consequences for some trial and

error. It was a time to discover my approach, my style, and my act.”

Consistent live performance is something that Mark has sworn by to really

cultivate an act, develop lines, and find ways to avoid potential problems

(all of which will happen at some point).

“Street

performing was very valuable for me,” says Mark. “It was like being

paid to go to school. You learn fast in that environment, and it helps you

to relax since there aren’t any real consequences for some trial and

error. It was a time to discover my approach, my style, and my act.”

Consistent live performance is something that Mark has sworn by to really

cultivate an act, develop lines, and find ways to avoid potential problems

(all of which will happen at some point).

The street provided that crucial woodshedding process. As street acts know, getting a prime spot is an important part of a successful show. Mark can remember paying the homeless from time to time to hold his spot overnight until he arrived early the next morning. Interestingly enough, several of the San Diego homeless have since been spotted doing Mark’s act in his absence (minus the throwing… and catching… and most of the dialogue).

Because of the raw and unstructured nature of street performing, there is great potential for the spontaneous and the unexpected. Anything can happen. One time in Boston’s Quincy Market, a full trash bag was heaved over the crowd and landed directly beside Mark, after which wandered a homeless woman. She stopped, stared directly at Mark, then bent over to pick up the bag as well as Mark’s discarded apple from the “eat the apple” routine performed earlier in the show. As she left the performance area with her prize, Nizer, ever the pro, remarked, “Mom, I told you not to bother me at work!”

“I don’t know what made more of an impression on me,” Mark recalls, “that situation or the time I got a $100 bill in my money hat. I thought it might have been a mistake so I packed up and left! You can buy a lot of macaroni and cheese for $100. However, I chose to buy one ounce of caviar instead. I’m no dummy!”

Once his act had matured, his next stops on the entertainment express were slightly glitzier venues — revue shows in locations like Las Vegas, Montréal, and Atlantic City, and cruise ships around the world.

Mark says the street “prepared me well for revues, since I was accustomed to doing several shows a day. The atmosphere was obviously different but whether I was in front of a street crowd in San Diego or on stage at Trump Castle, the foundation of my show was the same. The advantage was the guaranteed paycheck… and not having to yell as much.”

His opportunity to make the move away from the streets came after entering the American Collegiate Talent Showcase in 1982, placing high, and then entering a second time two years later and winning. His video from the showcase won the attention of an agency that plugged Mark into five years of revue shows. He found that these opportunities were an invaluable learning experience in terms of working with the technical and mechanical aspects of a performance, i.e. the theaters, lights, sound, etc. Two of the highlights of Mark’s career emerged during this time. He performed on several occasions with Bob Hope and toured as the opening act for Barry Manilow.

“They are both really nice,” Nizer says of the showbiz legends. “Barry is a true showman. He gave me advice regarding my show music and his drummer ended up writing a piece for me.”

Mark tells a touching story about flying in Bob Hope’s private jet (an experience we can all identify with, of course). After opening a show for the comedic icon, Mark found himself rushing offstage into a limo and then into Bob Hope’s private plane, complete with Hope’s famous profile printed on the side. Mark felt a sense of awe and childish giddiness, amazed by the entertainer’s lifestyle. The first few moments of the flight brought a dash of reality when Bob turned to his wife to ask in all sincerity, “Was I good tonight?”

“In overhearing that moment,” says Mark, “I found a very human quality within an atmosphere of fantasy. He’s Bob Hope and he killed that night, but he still questions himself, and that is humbling.”

Nizer also worked with George Burns. At a press conference they both attended, Mark asked George if he ever got nervous anymore. George said plainly, “If you don’t get nervous you don’t belong out there.” To work alongside entertainers of such grand stature and find that, behind everything, they are just people may have helped Mark develop his own attitude of not taking it all too seriously. His experiences with these and other celebrities were meaningful opportunities from which he learned and found inspiration to further develop his unique show.

Where

does he get his juggling inspiration? There are a handful of influences who

have moved Nizer and continue to inspire him today. Certainly Francis Brunn

has been a major influence in terms of his style and what Mark, personally,

finds interesting to perform and practice. The “Up the Leg” trick

mentioned earlier is an example of a Brunn move that seems straightforward

in concept (a ball rolls from the extended foot up the leg, over the back,

and then down the arm to the extended hand), but demands a lot of intense

focus, not to mention time, to perfect. Similarly, another Brunn classic that

interests Nizer is “heel kick to double-ball spin.” A ball is dropped

backwards from a neck-catch and kicked with the heel over the shoulder onto

the top of a ball spinning on the index finger. Both tricks are in the “really

friggin’ hard” category. Mark has devoted many years to these tricks

and performs them from time to time in his show. Like head rolls, a trick

Mark also enjoys, these Brunn examples utilize parts of the body that are

less often used in juggling. This adds to their allure and is part of the

reason Mark has chosen to study them. Mark, who knows Francis and has spent

some time with him in New York, says, “Today he can still do his tricks

better than I ever will.”

Where

does he get his juggling inspiration? There are a handful of influences who

have moved Nizer and continue to inspire him today. Certainly Francis Brunn

has been a major influence in terms of his style and what Mark, personally,

finds interesting to perform and practice. The “Up the Leg” trick

mentioned earlier is an example of a Brunn move that seems straightforward

in concept (a ball rolls from the extended foot up the leg, over the back,

and then down the arm to the extended hand), but demands a lot of intense

focus, not to mention time, to perfect. Similarly, another Brunn classic that

interests Nizer is “heel kick to double-ball spin.” A ball is dropped

backwards from a neck-catch and kicked with the heel over the shoulder onto

the top of a ball spinning on the index finger. Both tricks are in the “really

friggin’ hard” category. Mark has devoted many years to these tricks

and performs them from time to time in his show. Like head rolls, a trick

Mark also enjoys, these Brunn examples utilize parts of the body that are

less often used in juggling. This adds to their allure and is part of the

reason Mark has chosen to study them. Mark, who knows Francis and has spent

some time with him in New York, says, “Today he can still do his tricks

better than I ever will.”

Some of the other jugglers who have influenced Nizer are Sergei Ignatov, Dick Franco, Barrett Felker, Trixie LaRue, and Airjazz.

Technology has had a hand in influencing Mark Nizer’s show, as well as his life. He loves gadgets and is an avid computer user. In creating some of his routines he has had to practically learn a new field. His “Dimension Beam” routine uses “infrared light that converts motion to music,” using Midi. When he bounces a ball on his head you hear a wood block, cymbal, or whatever sound Mark has programmed in for that special area. When he jumps rope, you hear another sound and so on until he becomes a “Human Rhythm Composer.”

For his Laser Diabolo invention, he inserted two lasers into each diabolo so when they spin in the dark the audience sees a red cone of light whirling on stage and above their heads. During the finale, with the smoke machine running, two red laser-diabolos spinning, colored lights in the hand sticks, and a Mylar mirror reflecting the beams from behind, you can’t help but think, “Yeah, okay, that was a pretty darn good idea.”

Mark states that “inspiration can come from anywhere. I walk into all kinds of stores for ideas.” This is apparent in one of his most recent routines, in which he uses two industrial-strength fans to propel toilet paper towards the ceiling of the venue in a dramatic conclusion to his show — a mix of Ace Hardware and Bed, Bath and Beyond. Nizer claims, “Ideally I want to be in a hang-gliding rig of some kind and comically hover over the running fans as an homage to one of my favorite hobbies.”

Nizer rarely turns down a challenge, be it learning a Brunn trick or proving his MacGyver-like resourcefulness with new technological ideas. He is very prolific when breaking new ground with a fresh concept. It may take awhile for most people to flesh out a new idea and actually get it designed, let alone finished. Mark will literally mention an idea on Friday and by Sunday he has built a ridiculously complex working prototype that would have Thomas Edison and Nikola Tesla nodding in approval.

Mark has some strong

philosophical feelings regarding practice, routines, and live performance.

“Do it ’til you hate it,” he says of a routine you are trying

to perfect. What he has found very helpful is focusing on the building blocks

of an act and the trouble spots, along with repetition of a particular trick

and especially the transitions.

“The trick between the tricks — the transition — that is where

the routine becomes magical for me, when one trick can smoothly blend into

the next, as opposed to trick/cascade/ trick/cascade. It forces me to be more

creative and it looks cleaner.”

Nizer has a thoughtful

approach to routining, “getting from here to there” logically, creatively,

and gracefully. He appreciates a strong pose and sharp, deliberate moves,

a la Brunn. Mark combines that dynamic flair with a touch of dance and strong

movement which compliments his routines and gives them an identity. He feels

that “many performers should take a ballet class sometime. It helps give

you strong lines, and you will look more polished and refined.”

After spending countless hours in gyms, learning, trying, failing, succeeding,

bleeding, discovering, and achieving, Mark has this bit of wisdom to pass

on:

“I think a trick

is a feeling more than an act. Once you visualize it and begin to understand

it, you begin to really discover it and find confidence. You will almost always

notice that a trick slows down once you begin to get it. Knowing this when

approaching something new can be helpful.”

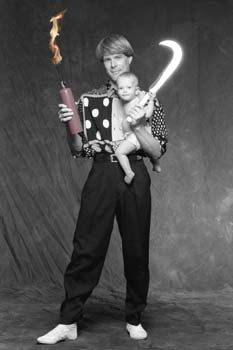

Mark has

had many accomplishments, but what has meant the most to him? “My wife

and three girls,” he says. “They help me to live life to the fullest.

In juggling, definitely winning the IJA Championships in 1990. That was significant

for me. Obviously, meeting some of the people I mentioned earlier, being on

television some, getting to travel and see so much of the country and the

world. Being a hang-glider pilot has given me a lot of joy over the years

as well. It is such an adrenaline rush, like doing five-club backcrosses…

so I’ve heard, anyway.”

Mark has

had many accomplishments, but what has meant the most to him? “My wife

and three girls,” he says. “They help me to live life to the fullest.

In juggling, definitely winning the IJA Championships in 1990. That was significant

for me. Obviously, meeting some of the people I mentioned earlier, being on

television some, getting to travel and see so much of the country and the

world. Being a hang-glider pilot has given me a lot of joy over the years

as well. It is such an adrenaline rush, like doing five-club backcrosses…

so I’ve heard, anyway.”

In recent years Mark has been working the college market and performing arts centers. In February of this year he presented his full show at the Kennedy Center in Washington D.C. It was broadcast live over the Internet — the first live streaming-video juggling performance ever.

“It was a wonderful opportunity to combine technology with entertainment,” he says Mark. “The only problem was, if I dropped, the whole country has the ability to see it and the video footage is archived forever.” To relieve the pressure Mark decided to drop a ball on purpose right from the beginning to get it out of the way. “There, I feel better, now we can move on!”

Performing for dozens of colleges throughout the year, Mark has found an approach that this age group responds to well. He admits it is a hip crowd, and one that he has felt comfortable taking some risks with. “Performing for a college is like a combination of the street and the stage,” Nizer believes. “Students respond to a lack of structure since their current world involves so much structure.” Of college students, Mark says, “I am one of them, really, just a little older. When we identify with each other everyone wins.”

It is no easy task to win acceptance in an atmosphere that can be described as, “Guilty until proven funny.” His show music, attitude, and spirit reflect a youthfulness that is accessible to all ages. Mark has a natural mix of qualities that help grab the audience’s attention and interest and hold it for up to an hour and a half.

Mark Nizer is hip,

his music is catchy and current, the sunglasses he wears during his show are

stylish, his tricks are dangerous (diving forward roll with torches), and

one of his catch phrases is, “the juggler your mother warned you about.”

His direction in juggling is toward new ideas. Innovation and discovery are

therapeutic for him, and pleasing for audiences.

“I started very technical in my practices, hours and hours a day, and

I still practice some of it,” Mark relates. “But I don’t think

audiences really know the difference. An amazingly technical routine to them,

I imagine, is like the scene in Close Encounters when the spaceship lands

and aliens step out. The people watching are thinking, ‘We know we are

in the presence of something interesting and exciting… we just don’t

know what it is.’

“My goal is to

find new ways to connect with them and still be interesting, exciting, a little

artsy and a little different, but accessible. People have seen a lot of toss

juggling through the years. I love it, but I am also fascinated with new ideas.”

He admits he has a whole garage full of failures. No, he isn’t referring

to family members, but rather ideas that didn’t work or haven’t

worked yet. He feels that he can adapt to some of the new ideas quickly, because

he has had such a solid foundation of practice with the fundamentals and more

traditional juggling.

Even Mark’s promotional material reflects creativity, fresh ideas, and as mentioned earlier, not being taken too seriously. From 3-D glasses with his 3-D bio pages, to the Mark Nizer Paper Dolls (have your parents help put them together), to Mark Nizer temporary tattoos. Naturally, there is also an extensive website (www. nizer.com), complete with tour information, prizes, and a game.

“I have done a few things,” says Mark. “I’ve raised a family, I’ve flown hang-gliders at several thousand feet, I’ve built a backyard deck, I’ve driven a Ferrari. But I do get a huge rush from juggling. I find it really satisfying. It is a necessary outlet for me and it gives me a rewarding sense of balance in my life. And I love it. I love to push myself in everything that I do. Also, if there’s a talent show in Heaven, I want to be ready.

“If you do get a chance to drive a Ferrari, though… Woo-Boy!! Heck of a ride!”

Bryson Lang is

a juggler/comedian and guitar player living in the Los Angeles area.

He

can rock-skip any rock that he can hold in his hand.

Juggler's

World: Vol. 42, No. 3

Juggler's

World: Vol. 42, No. 3U.S. Nationals Championships

Nizer's Last Minute Decision Proves Fruitful

by Dave Jones

The 1990 U.S. Nationals Championship will undoubtedly go down in the books as one of the best overall displays of juggling talent. Eight competitors each performed high-quality shows and entertained the audience with a wide range of props, styles and personalities. The champion, Mark Nizer, became king of the hill for 1990 by using the talent he has developed during the last 15 years and, more importantly, the experience of more than 10 years of performing.

"The real advantage I thought I had was that I am a professional and I perform every day," he said. "I do a lot of stage shows so I'm used to that environment and I immediately felt at home. But I think the points in performance were more important than anything else because, obviously, everyone was doing all this fantastic stuff."

Performing well in the competition and rising above the others was a difficult task for Nizer, one that was made even more taxing by the fact that he did not decide to compete until two days before the championship. Using only a few of his props and a borrowed Janet Jackson tape (a contrast to the classical music he normally uses) he was able to get through the preliminaries and into the show.

Nizer said he had little difficulty deciding what to use for his seven-minute competition routine. "You know what jugglers like. And I wanted to do a little talking because it makes me relaxed, and it takes the bite off the audience," he said. He opened with three balls, performing a smooth, jazz-inspired routine to classical music. Next came a headroll routine which began by throwing one of the three soft balls high into the air straight to a series of head bounces. Perhaps the most impressive trick of Nizer's show came next. He performed a backroll while spinning a ball on each of his index fingers and another on a mouthstick.

Nizer followed the backroll with a routine inspired by one of his juggling idols, Trixie Larue. He juggled four rings and a volleyball, performing a series of head bounces with the ball, and placing the rings around his neck.

Nizer wanted to perform the trick as something of a tribute to Trixie, but in hindsight, he admits that may have been a poor choice. "That was a bad move. I shouldn't have done it, because it's pretty new and I'm not really confident with it. But, I got lucky." He ended with three clubs, a decision which was inspired by the fact he'd been working on a cruise ship for six weeks, which had left his four-club routine and all of his high tricks quite rough. The one exception though was the backcross pirouette which he used as his final trick. "I hadn't done that in six weeks, but I had to do it because I gagged it in '84," he said.

The desire to win and avenge his loss in 1984 added a little

pressure to the competition for Nizer. But what added even more was what losing

might mean, given his status as a professional performer. "My ego was on the

line. It's really scary, when you're doing this for a living, to put your

reputation on the line and compete. That's why I think a lot of professionals

don't enter, because there's a big risk if you don't win," he said.

The desire to win and avenge his loss in 1984 added a little

pressure to the competition for Nizer. But what added even more was what losing

might mean, given his status as a professional performer. "My ego was on the

line. It's really scary, when you're doing this for a living, to put your

reputation on the line and compete. That's why I think a lot of professionals

don't enter, because there's a big risk if you don't win," he said.

But while the competition may have been somewhat stressful, Nizer's overall experience at the festival was anything but. Having been away from the scene for six years, he was pleased to renew and start friendships. He said, "A lot of these people I've known for 12 years. It's really strange to see them, and how we've all changed through the years, and how we haven't changed. It's like coming home to a big family."

He was immediately interested in getting caught up on the development of the organization, and is very interested in the discussion of changing the format of the championships. "The IJA was my whole reason for juggling when I was a kid," he said. "I juggled for the championships, so that I could do better and compete."

Since the competition fueled his desire to practice and improve, he naturally questions whether the proposed "showcases," which would not involve competition, would similarly inspire young jugglers of tomorrow. He commented, "I think that would be great if it would work, because I agree that it's hard to judge who's better than who, and what trick is better than what."

It is not at all uncommon to meet professional jugglers who are primarily concerned with their own careers, and who have little or no interest in discussing juggling as an art, let alone what is going on in the IJA. Mark Nizer is very much the opposite. He spends a great deal of time thinking and talking about juggling on a level beyond tricks and routines.

"I think the great jugglers all have something slightly wrong with them. It's an obsession to really want to be that good at something," he said. That statement describes well his own relationship with the art of juggling. When you see him perform, the talent that he displays provides ample evidence of his dedication. But when you meet him offstage, his love for juggling and many of its practitioners becomes more strikingly clear.

Nizer learned to juggle 15 years ago at the age of 13. His mother enrolled him, his sister and brother in an adult education juggling class to give them an outlet for their excess energy. While his siblings never got hooked on it, learning to juggle had a profound effect on Mark, one which he is not sure his mother has liked. "I think she regrets it, in a small way as she didn't realize what would happen when she did it. I was well on my way to being a generic all-American child," he said.

It is during this formative period of a juggler's life that Nizer thinks adversities can have a very inspirational effect on one's future. "In my case, the year I learned to juggle, my father died. And I kept asking myself 'did he really live for the moment?' He never did what he really wanted to do, because he was trying to switch jobs. So as a kid, I just said 'I'm going to do it, I'm going to live for the moment.'"

Since then, Nizer has definitely lived for the moment, with juggling as the key to the experience. He describes himself as a person who could be content staying in the same place, doing the same thing his whole life. "But, I can't do that, my job has forced me to be constantly changing," he said.

Nizer grew up in Massachusetts, and his first inspirations came from performers in that area. He would go to the MIT juggling club and watch various jugglers, including Dario Pittore, one of the first jugglers who inspired him. He also admired the Fantasy Jugglers and Slap Happy, who performed in Boston.

The real inspiration, however, came after he went to Boulder, Colorado, one summer to street perform with a partner, Alan Streeter. The time he spent in Boulder was invaluable and the people he met - including Airjazz - influenced him greatly. "It hit me at just the right time in my life. It brought the performing of the East Coast together with the technique of the West Coast," he said.

Perhaps Nizer's most important connection made that summer was meeting Barrett Felker. Working out and learning from Felker "opened a whole floodgate of potential." Nizer is quick to point out that jugglers need inspiration from other jugglers whose abilities are within the realm of possibility. He says that someone like Sergei Ignatov does not work as an inspiration for most jugglers because what he does is too far out of reach. But someone like Dick Franco, who was an inspiration to Barrett Felker, is within more people's reach. "Dick Franco inspired a lot of jugglers because he was the connection between Ignatov and three balls. He was the semi-reachable goal," Nizer said.

After that summer in Boulder, Nizer's next big step came when he transferred to San Diego State University and began street performing in Balboa Park. He worked the streets of San Diego for five years, a period during which he learned a lot about performing. When he started, he was "a scared little kid who just screamed every line." But he did improve. "You cannot beat that for training... It made me find my character, slow down, and start writing a lot of comedy."

He did not do it all on his own, and had help from seasoned street performers like Ben Decker. "Ben helped me learn to write. He took me to San Francisco, and showed me all the street performers... And he taught me to be original, which I think is the most important thing in any show."

Also during this time, Nizer learned a great deal from Edward Jackman, another juggler with whom he worked, performing together for two years in Balboa Park, as "Two Guys Who Juggle." They dressed in blue gas station attendants outfits, and frequently performed two new shows a day. "We would do one show, then decide it stunk and come up with a new one."

Since those days, Nizer's career has carried him to many different places. He has worked in Atlantic City, performed at Lincoln Center, opened for stars such as Ray Charles and Bob Hope, done comedy clubs and cruise ships, and many college shows. Recently, he has also begun to hit it big in the television market, an accomplishment which he feels is partly the result of getting a manager. "It really helps to have someone speak for you, whether you need it or not," he said. "The fact that someone else believes in you enough to speak for you, I think makes a big difference in television." Appearances on Arsenio Hall, Comic Strip Live, Good Morning America, and Everyday with Joan Lunden are some of his recent television gigs.

Even more enjoyable than the performing successes of the past few years has been the chance to meet some of his juggling idols, including Francis Brunn and Trixie Larue. He said, "Francis Brunn is the greatest juggler that has ever lived and ever will live, as far as I'm concerned. Even as he gets older, he still practices like a total maniac... What he loses in speed over time, he makes up for in style and control. He is so friendly and open... It's inspiring when you meet your idols and find they are just as great, if not greater than you hoped," said Nizer.

Despite the great history that juggling has, and the long line of talented performers like Trixie and Francis Brunn, Nizer is quick to remind us that outside of the juggling community the art is not so highly respected. "Juggling really does have a bad connotation to it in the entertainment world," he said. "A lot of people, as they grow as jugglers, get further and further away from calling themselves a juggler." He points to a comment made by Pat Sajak, on his since-cancelled show. Sajak said "If it weren't for mimes, jugglers would be the lowest form of entertainment."

"Whether we like it or not, that's what the public thinks," Nizer said.

Well, despite what the general public may think, we know that juggling is the greatest thing on the planet. And, with people like Mark Nizer performing and bringing the skills to the attention of the masses, there is still hope that someday everyone will come to the same realization.

Dave Jones is a Juggler's World staff writer who lives in Allentown, PA

Practice

Pays Big for Nizer in College Talent Search Contest

Jugglers World Magazine

By Bill

Giduz, editor

May 22, 1982

How does $1,000 for a five-minute act sound?

Mark Nizer from Durham, NH, walked away with that overwhelming sum with a third place finish in the All-American Collegiate Talent Search competitions held at New Mexico State University in January.

Now, how does practicing your juggling I I hours per day four days per week sound? That's the schedule Nizer follows to keep in shape to win the big money and hopefully make a professional career of his considerable talent.

Contacted at the University of California San Diego, where he is spending the academic year on an exchange program from the University of New Hampshire, Nizer talked confidently of his accomplishments and future plans.

"I think I'll take time off to juggle after this semester," he said. "My heart's just not in my studies. I've applied for a job with the 'Barnum' production, and have an option to do a USO tour this summer.

"What I'd really love to do is a Globetrotters tour. When I was learning to juggle, that seemed like the ultimate. Of course, I'd like to work in Las Vegas. I'm sure I can do it, too; confidence is what it takes to make it."

His confidence comes from experience gained in the long practice sessions and many stage and street performances. On weekends, he and Edward Jackman team up in San Diego's Balboa Park to show audiences some of the best juggling they'll probably ever see. It's historic ground, Nizer pointed out; the same spot where Dick Franco and Kit Summers launched their careers. "It's got a great heritage, but you can't get rich passing the hat there," he noted.

Nizer and Jackman work together to gather a crowd, then perform separately. Nizer described his street act. "I begin with a fast three ball routine. I really love three balls because you can express yourself so well. I'm working on character and personality a lot, and three ball tricks are a good medium for that.

"Then I do ping pong balls with my mouth two generally but three if I feel good. Then a 12 cigar box balance and a three cigar box manipulation. I do a somersault into catching a fire club, then five and six rings and three, four and five clubs. I end with a torch, machete and apple on a six-foot unicycle. I catch the apple on the machete, jump off the unicycle and give it a big 'Ta-Da!' to end the show."

Nizer loves to pirouette, and works them into the act wherever possible. He can do a pirouette juggling five rings, and says he is working on one with seven. "I'm breaking a lot of fingernails practicing that one!" he said.

He feels like he'll never want to juggle more than seven objects, concentrating instead on the showmanship and style he thinks is needed for a successful career.

Because of the beautiful weather, it's hard for a New Englander to concentrate on any kind of work in San Diego, Nizer said. But while he may let the academic homework slide, he rigorously adheres to his juggling practice schedule in the UCSD gymnasium.

"I moved to an out-of-the-way comer just the other day to avoid other people," he said.

"I found when people were watching I'd practice tricks I can already do, whereas I need to practice new material. So now I do the things I want to do but can't yet."

The I I -hour day is meticulously divided into blocks of time for working on separate tricks. After a half-hour stretch to warm up, he works on rolling a single ball around his head for a solid hour. Then it's four club back crosses for an hour. Next, five club double spins for an hour and triple spins for another hour. Then he repeats the whole sequence.

"I try to work I like a dog, and end up drinking a lot of water," he said. When he's tired, he works on cigar box tricks over the bed in his dormitory room. It's strenuous work, but Nizer knows there is no easy road to juggling fame.

|

||||||||||||

Copyright Mark Nizer 1998-2013 ©

All material on this page may not be used in any manner without prior written permission from:

Mark Nizer™ and/or Active Media Group™

Contact Site Administrator: Active Media Group.